Fez - After many years of struggle by women’s organizations, the situation of women in Morocco has improved, thanks to the adoption of several reforms.

During the last two decades, Moroccan women have been calling for equal rights between men and women. Their efforts have given birth to many triumphs and contributed to the improvement of the status of women in Morocco. Theoretically, Morocco has some of the most improved laws for women’s rights in the Arab world. However, these new laws are not applicable throughout Morocco, especially in rural areas.

Starting from the 1990s, women’s struggle for reforms achieved a concrete victory and began to gain momentum. Conducted by the Union of Women’s Action (UAF), a petition calling for the reform of the Personal Status Code and Sharia-based family law collected signatures of one million women. This petition demanded the government to sign the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), and to use its articles to amend the country’s Moudawana (the official family code that dictates the roles and relationships between men and women within the family). Consequently, Morocco ratified the CEDAW in 1993, but with a number of reservations. Moreover, during the last decade, the Moroccan government introduced more reforms to the Personal Status Code.

The terrorist attacks in Casablanca in 2003 represented an opportunity for the Moroccan government to reform the Moudawana, in spite of the objection of the Islamist leaders and the accusations that the king introduced these reforms under pressures from the European Union and the United States. Despite the fact that the reforms scored a victory for the Moroccan women movements, Islamists, including women, strongly opposed those reforms. The spokeswoman of Justice and Charity Islamic Movement, Nadia Yassine, described the reforms as representing the interests of foreigners and international feminist movements, rather than the legitimate will of the Moroccan people.

The reformed version of the Moudawana grants men and women equal rights within the family. Husbands and wives now have equivalent rights in house management, family planning, children upbringing, and legal cohabitation. The legal minimum age for marriage for both men and women is 18 years (it was previously 15 years for women). Special cases of marriage under that age now require permission from a judge. Also the free consent of both spouses is now required by law and women no longer need permission from a male guardian to marry.

The Moudawana does not entirely prohibit polygamy, but rather includes measures that make it very complicated. Those who want to marry another wife must obtain a judge’s permission and provide a documentary evidence of their financial situation. They must also certify that all their wives will receive equal treatment, and that their first wife (or wives) has given her approval. Since the reforms were introduced, the number of new polygamous marriages has decreased. Furthermore, the new family code eradicated the concept of repudiation (that is to say, the husband’s right to unilaterally divorce his wife) and gave women the right to divorce on the same grounds as men.

Morocco further amended the Family Code in 2007 by passing the Nationality Code, which granted Moroccan women married to foreigners the right to pass on their citizenship to their children. In the past, only fathers possessed this right.

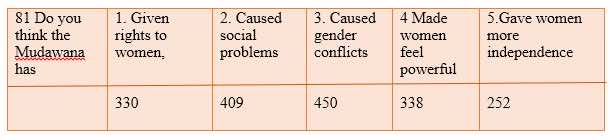

Dr. Khalid Bekkaoui recently conducted a survey on 1,271 respondents who belong to different parts of Morocco. When asked their opinion about the Moudawana, the respondents’ answers were as follows:

The answers do not show big differences, but they show that the majority of respondents do not have positive opinions about the Moudawana. They think that it has caused gender conflicts and social problems. However, a significant number of respondents, about one third, have positive attitudes towards the Moudawana, stressing the fact that it has given women more independence and made them more powerful. The large number of respondents who have negative opinions about the reforms of the Moudawana could be related to the fact that Morocco is still a patriarchal society, which refuses to reach equality between men and women. Women in the countryside are subordinated to their husbands and fathers; they have no agency. They are not even aware of their legal rights. The majority of them have no idea about these reforms.

The answers do not show big differences, but they show that the majority of respondents do not have positive opinions about the Moudawana. They think that it has caused gender conflicts and social problems. However, a significant number of respondents, about one third, have positive attitudes towards the Moudawana, stressing the fact that it has given women more independence and made them more powerful. The large number of respondents who have negative opinions about the reforms of the Moudawana could be related to the fact that Morocco is still a patriarchal society, which refuses to reach equality between men and women. Women in the countryside are subordinated to their husbands and fathers; they have no agency. They are not even aware of their legal rights. The majority of them have no idea about these reforms.

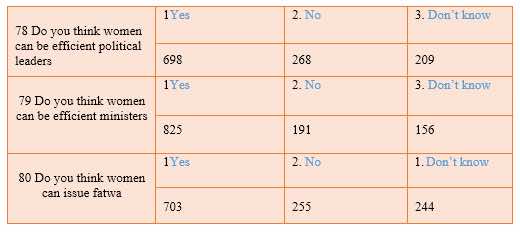

In other questions about whether respondents think that women can be efficient political leaders, efficient ministers, and whether they can issue fatwa, the majority of the respondents (around two thirds) responded with “yes”. That is to say, they think that women can be good political and religious leaders. The following chart shows their answers:

This shows that Moroccans have positive opinions about women; they think that women, like men, can be good leaders. However, some Moroccans, as the survey shows, have negative opinions about the reforms of the Moudawana. They probably think that the Moudawana has deviated from religious teachings concerning the relationship between men and women and the reforms of the Moudawana have deprived men from some of the rights that religion has given them. Another reason could be related to the fact that some people (especially Islamists) think the reforms of the Moudawana were imposed by Europe and the U.S. , and therefore serve external agendas.

When the Arab Spring reached Morocco, the February 20 Movement, which led the protests against the Moroccan political system and demanded reforms from the part of the King, included several women activists. In March 2011, the Government Agenda for Equality was ratified, and on June 17, King Mohamed VI expressed support for a constitutional reform that would enhance the separation of powers in government and support gender equality. The referendum outlining these reforms took place on July 1, and passed with 98% of the Moroccan electorate. The new Constitution prohibits gender based discrimination and adopts new laws that reinforce gender equality in fundamental rights and freedoms.It offers protection of individual rights and gives special recognition to women’s rights. Article 19, for instance, entitled “Honor for Moroccan Women,” makes men and women equal citizens under the law; specifically, it grants men and women equal social, economic, political and civil rights. It also created the “Authority for Equality and the Fight Against All Forms of Discrimination,” charged with the function of putting into practice the constitutional recognition of equal rights. For the women’s rights movement, at least on paper, this event represented a long-awaited realization of twenty years of activism.

While these major reforms have been applauded by feminists in Morocco and other countries, women’s movements are still working hard to ensure the implementation of these reforms throughout the different parts of the country, and to call for additional legal changes. Recently, ADFM (Association Democratique des Femmes du Maroc) launched the campaign “Equality Without Reservation,” a regional campaign to compel the government to respect all the rights enshrined in the CEDAW. The biggest challenge to the women’s movements has been the inability to integrate these reforms throughout the country.

So although the Constitution has allowed some progress in theory, there hasn’t been much difference in practice, especially in rural areas. The ongoing obstacle of women’s illiteracy implies that a substantial number of Moroccan women are unaware of the efforts being waged on their behalf by their educated and mobilized counterparts, and they remain oblivious to their newly gained rights.

© Morocco World News. All Rights Reserved. This material may not be published, rewritten or redistributed