![Crossing Borders in Diwan Sidi Abderahman Almejdoub- A Theatre Within a Theatre]()

By Abdeladim Hinda

Kenitra - Quiet hamlets in the Arif mountain valleys, spacious pastures on the slopes, lakes and dams here and there upheld in the chalice of the hills, fields green or yellow verging toward the blue Northern Mediterranean Sea and the Western Atlantic Ocean, villages and towns drowsy under the noon sun of July and then alive with passion cities in which, amid dust and dirt, everything from cottage to masjid seems beautiful— this for thousands of years has been Morocco. Yet it was only until 1967 that Saddiki observed, under the light of his theatrical experiences of adaptation and translation, the beauty of Morocco along with its antique legacies which constituted the culture of its industrious people. In one word, to Saddiki Morocco appeared in due course to be a tempting time-honored legacy, fit for dramatization, fit for celebration.

Remarkably, the failure of his experience of Theatre of Workers unexpectedly turned itself into a denial consciousness raiser. That is to say, Saddiki “realized that the series of plays he adapted, translated, or moroccanized were not projecting his deeply rooted festive instincts.”[1] It is here that Saddiki offers a comment on his disavowal of the Western repertoire of theatre making:

The story started as a result of my refutation of the texts that I had translated and adapted from foreign theatres. After adapting about thirty plays, I was overwhelmed by the idea that this is a transplanted theatre that does not reflect the inner self of Moroccans. Then, a new journey started along with people, their surroundings, collective imaginary…I enjoyed people’s stories and myths…It was in this context that I discovered the 16th century poet “Almejdoub.” His poetry was not written, but transmitted orally amongst people in every Moroccan home. Then, I started assembling his verses and re-writing them in a dramatic way. That was the birth of the play entitled Sidi Abderahman Almejdoub, a drama that won an exceptional success in Morocco.[2]

The play has been performed within the parameters of al-halqa, which in all its diversity has been a vital source of artistic delight and entertainment, as well as a means of spacing cultural identity. In other words, besides its aesthetic aspects -given the fact that it should be conceived of as a performance event- it is a medium of information and circulation of social energy, a social drama and a subsidiary school whose syllabus is as fluid as its rich repertoire. In sum, al-halqa contributes to the representation of historical consciousness and cultural identity, through formulaic artistic expression.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, a number of the leading dramatists of the Arab world began to return to indigenous performance traditions for inspiration and as a counter-balance to the previous, almost total dependence upon European models. Such an approach was propounded by Tawfiq al-Hakim, the leading dramatist of the Arab world, in the preface to his best-known play, Ya Talià al-?ajara (The Tree Climber), published in 1962, which called for a “popular, nonrealistic theatre.”[3]

Pr. Khalid Amine and Marvin Carlson note that “Al-Hakim’s suggestions were picked up and elaborated by the best-known of his immediate followers, Youssef Idriss, in an influential series of articles titled “Our Egyptian Theatre,” published in 1965 in the leading literary periodical al-Katib.”They continue,

Here, he advocated a turning away from the traditional European models to seek inspiration in local and folk manifestations—in particular, the medieval Arabic oral, rhymed narration, the maqama, and the samir, a popular festival in which villagers gather to improvise entertainments involving singing, dancing, and impersonation. Idris’s most popular play, al-Farafir (The Flipflops, 1964), was published with extensive prefatory notes related directly to the arguments in the al-Katib articles.[4]

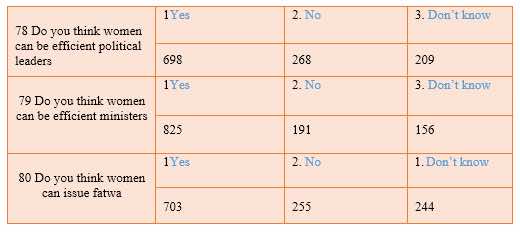

Like Idriss, Saddiki too was influenced by Al-hakim’s new theatrical trend. He revived Al-halqa performing spectacles. From then on, Al-halqa has become widely employed in the modern Arabic theatre as it provides a distinct alternative to the traditional European proscenium stage. In light of this, Pr. Khalid Amine maintains that “Saddiki’s theatre is an exemplary first instance of festive hybridity. After consuming numerous adaptations from the Western theatre, he inaugurated a new approach to theatre making in Morocco.”[5] Indeed, his play diwan sidi abderahman almejdoub exemplifies the first festive theatrical enterprise in post-colonial Morocco. Saddiki construed it in the ‘in-between’ space, that is to say, between western theatre and Moroccan ‘pre-theatrical forms.’ For the first time in the brief history of Moroccan theatre, Saddiki transposed (see fig.1) al-halqa, as an aesthetic, cultural, and geographical space, into a theatre building as the space of the Western Other “(transplanted in Morocco as a subsidiary colonial institution).”[6] Pr. Khalid Amine continues that “Sidi Abderahman Almejdoub is a play conceived in an open public place. Its opening refers us to its hybridized formation through its persistent self reflexivity, as a device of projecting the mirror of the performance itself.”[7] The play is “situated in jemaa el-fna as an open site of orature and a space of hybridity itself.”[8] Its structure is “circular rather than linear.”[9]

[caption id="attachment_134994" align="aligncenter" width="600"]

![Fig. 1: Indoor halqa performance. (Photograph by Khalid Amine.)]()

Fig. 1: Indoor halqa performance. (Photograph by Khalid Amine.)[/caption]

Summary of the play

The play opens with Narrator 1 and Narrator 2 bestowing praises and beauties upon the city of Marrakech, and setting up the drama’s décor. The storyteller comes in and starts to recount the narrative of “The Prince and the Bondmaid” to create the climate of al-halqa. Then, Narrator 1 presents himself, saying he belongs to the 14th century. A young man belonging to the 20th century of the Hegira asks him about the locale of Jama’e Lefna. The young man seems to be interested in Jama’e Lefna as it signifies a place for leaning for him. Narrator 1 and Narrator 2 go about defining the different spectacles they are going to offer: the confectioner, Chi:kha, Ali and the Tyrant’s Head, Sellers of Herbs, and Sorcerers, etc. However, they decide to devote their al-halqa for commemorating Sidi Abderahman Almejdoub.

Narrator 1 and Narrator 2 begin to organize al-halqa. They present the character of Almejdoub to their audiences, and refer to his wise sayings every now and then. However, Almejdoub appears and points to his place of birth. Then al-halqa organizers join in to highlight his life in Fes and Meknes. In Farewell lawha, Almejdoub bids farewell to his wife, Tona, after he has decided to leave Morocco. Narrator 1 and Narrator 2 inform us that he is heading for Mecca to perform the pilgrimage.

On his way to Mecca, Almejdoub traverses the Land of Shall whose inhabitants brush aside their responsibilities and postpone them instead. Moreover, they are less inclined to good, hospitality, and generosity. Seeing they are good for nothing, Almejdoub leaves them and heads for Tunisia. He observes that the occupants of this habitat are caught up in the love of women, who have reeled them into their web of control, and left them singing words of passion and names of women, while turning a blind eye on colonialism, which is devouring them unmercifully.

Armed with faith and patience, he begins to roam the earth, north and south, west and east, hoping to overcome his loneliness. Unexpectedly, he falls captive in the hands of Christian pirates, who throw him in prison where he falls in love with a girl. He hopes that she would follow him to his land where she could convert to Islam. After traversing a mountain of troubles, he gets to the land of prophecy, and there he delivers a poem in which he praises the Messenger of Islam, Muhammad (PBUP). When he finishes his delivery, a group of people go about reciting in great unison the famous poem The Full Moon Has Risen for Us, which the first generation of Muslims song in welcome of Muhammad, in order to associate Almejdoub’s migration with that of the prophet (PBUH).

Now back in Morocco, he finds out that everything has changed due to the tyrannical colonialism. Blessed with his presence, the land recovers, kicks out the invaders, and regains its normal station. Meanwhile, we are taken back to the climate of al-halqa. A “makhzani” person approaches Narrator 1 inquiring about al-halqa’s warrant. He becomes a partaker in the unfolding halqa, putting a plethora of questions to Almejdoub, who answers with lines from his quatrain, lines that reveal women’s tricks and malice. This arouses a feeling of defense in the women present, and make them denounce those anatomizing claims to rehabilitate themselves.

As al-halqa comes to an end, the narrators start to gather alms from the audience. A new halqa unravels in which a man performs a spectacle of merry with the aid of his monkey. As he does not have al-halqa’s license, Almakhzani sends him away and the attendants buy him some tea and sugar. Now the narrator starts to explain Almejdoub’s sayings about the rooster, the horse, the donkey, the mouse, and the wolf, drawing his audience’s attention to the wisdom and symbolism dormant in these sayings. The talk changes to include herbs and fruits. Meanwhile, a woman inquires about Almejdoub’s knowledge, and he turns himself into a fortune-teller, revealing her past and prophesying her future.

A discussion about women together with their beauties and evils is resumed. At this stage, Almejdoub is shown spellbound and smitten by Rabha’s charms and beauties. He thus delivers a poem about her, flattering her beauty despite his friend’s cautioning. However, his friend’s advice turns out to be advantageous as he comes to the realization that she is of a doubtful and opportunist nature. This realization leads him to ponder about human relationships. It also leads him to think of Tona, his first wife, whom he misses very much.

At this point, the audience, including those who organize al-halqa, inquires Almejdoub about quietness and its wisdom, money and its influence, friendship and its fate, repeating in harmony some of his sayings every now and then. However, Almejdoub becomes blind and enters a difficult phase in his life, ending up working for farmers as a shepherd. As his health deteriorates, he decides to visit Holy Shrines to seek the grace of its hollowed dead Sheikhs. Indeed, he drops The Shrine of Sidi Al-hadi Ben Issa a visit not to heal himself from the insanity of which he had been accused, but rather to observe it in his society. He says

How many men, with flawless conscience,

Pretended to have lost reason and every virtue

Neither they understood nor discerned his intentions

But to Ben Issa drove him people of good feature.[10]

After having experienced a spate of troubles of all colors and types, and after having rejoiced the good and forbade the wrong, Almejdoub foretells his end. Like an ascetic person, he goes alone to meet his fate. At this stage, we are taken back to the climate of al-halqa where Narrator 1 asks the young man belonging to the 20th century whether he has liked what he saw and heard, and the young man assures his questioner that he is interested in poetry in general and the poems of Almejdoub in particular. On hearing this, Narrator 1 maintains that this is glad tidings for Almejdoub is still alive in our cultural memory. The young man wishes to meet Almejdoub in his dream, and Narrator 1 tells him to love the people and serve them well and surely he would feel Almejdoub within himself.

The play would have been finished at this point. Yet Said Saddiki composed a poem in which he states his opinion about Almejdoub. In brief, finalizing the play with such a poem implies that the past is extended to include the present, and the tradition modernity, reconciling between the two in a festive moment, thus inviting us to return to our traditions, to our origins.

Analysis of the Play

The play is divided into four sections, each one bearing the word tarkib, meaning assembling, as a title. Each tarkib consists of several lawhat, meaning tableaux. To be exact, the first tarkib is made up of fifteen lawhat, the second of seven, the third of four, and the fourth of seven. In other words, the play bears much resemblance to its classic counterpart in that both of them are structured in four sections. From the vantage point of classicism, a chapter implies transformation at the levels of place and time. From Saddikian point of view, a tarkib is much more similar to classicism’s chapter in sense in that the play’s first, second, and third tarakib (plural of tarkib) unfold in Jama’e Lefna’s Square, while the fourth unfolds in a place supposed to be in Meknes yet through al-halqa.

There is, in my opinion, a reason behind such a systematic structuring of the play. I think the dramatist aimed at realism when he featured his hero’s life just as he lived it in reality. For that reason, he dedicated the first tarkib to present the person of Almejdoub, the second to reveal his quatrain, the third to speak of its dissemination, and the fourth to outline the hero’s last days. Thus, laying out the play into four sections is in fact an act of unfolding Almejdoub’s life into four phases, each phase containing some lawahat that characterize it. These lawahat are listed as follows:

1) Al-halqa

2) Presenting the Person of Almejdoub

3) Farewell

4) Transformation

5) The Land of Shall

6) Transformation

7) Tunisia

8) Alienation

9) At Sea

10) Prison

11) Pilgrimage

12) Colonization

13) Salvation

14) Al-halqa

15) The End of Al-halqa

16) Al-halqa

17) Almejdoub’s Sayings

18) Women

19) Almejdoub and his Friend

20) Farewell

21) The Second Wife: Rabha

22) Tona

23) Almejdoub’s Sayings

24) Almejdoub’s Tribulations

25) Almejdoub Becomes Blind

26) A Visit

27)Sidi Al-hadi Ben Issa with Insane and Leprous People

28) The Other Community

29) Almejdoub’s Visit

30) Farewell

31) Al-halqa

The play ends with ahalqa to show that life, which is lived within a recurring circle, goes on irrespective of the sorrow and happiness it contains. In this case, the play’s ending signifies that if Almejdoub’s contemporaries did not recognize his worth and significance, subsequent generations, including ours, have done so thankfully. Pr. Khalid Amine observes that

Saddiki’s halqas are most of the time semi-circular rather than circular. And this very fact is due to his festive tendencies to engage the audience in the making of spectacle rather than being seated on a hypnotized auditorium that is already divided by a fourth wall in western Bourgeois theatre.[11]

The halqa of Almejdoub is presented after a series of other related halqas. This shows Vilar’s advice to Saddiki: “when you go back to your home country, forget all what you have seen here and remember just the technique.”[12]

Saddiki lists his characters according to their worth and significance, and according to their acquaintance with Almejoub. For that reason, he bestows importance upon his wives and lover, Narrator 1 and 2, First Woman and Second Woman, Ashab Alhalqa (al-halqa organizers): Aziz, Mostapha, Mohamed Elhadi, and then upon an amorphous constellation of people such as prisoners, pilgrims, pirates, insane persons, mystics, sailors, Tunisia inhabitants, inhabitants of the Land of Shall, whores etc.

The drama’s central character is Almejdoub. In Arabic, almajdoub, literally meaning leprous, is an epithet sticking often to mystics and saints. Indeed, in our culture some people were called majadib (plural of majdoub) because they were known for their mysticism and renouncement of worldly pleasures. They abstain from the beauties of life, seclude themselves, and live in austerity. There is a line in the drama through which Almejdoub conveys all these characteristics:

Almejdoub: I am mejdoub but not insane, living with my internal state of mind. I in the Saved Slate read that passed and that is to come alike.[13]

In this sense, he bears much resemblance to the person who declined to drink from the River of Folly to be ironically accused of insanity by those who drank from it. Certainly, he feels himself alien among his kinsmen, who for years and centuries turned a deaf ear on his wise sayings. This fact is beautifully captured in a scene in Wole Soyinka’s The Lion and the Jewel as it seems to be common not to honor wise people:

Sidi: These thoughts of future wonders –do you buy them or merely go mad and dream of them?

Lukunle: A prophet has honor except in his own home. Wise men have been called mad before me and after, many more shall be so abused.[14]

Almejdoub tries hard to pour the waters of his soul to wash the feet of his people, but they trample him with their feet of ignorance. He says in this regard,

Almejdoub: I appeared to them black and sealed, and they thought I lacked everything virtual. Yet I am like a written book which contains numerous advantages.[15]

Almejdoub seems to have pondered about the universe and the life its contains, human relationships and the way they work, Man and his ways and airs, and all things life offers. Moreover, his speculation includes the creatures of women about whom much is said in his poetry. But to measure things right, one should not rush to judge Almehjoub as anti-women or in today’s terminology anti-feminist for he distinguishes between there types of women. They are manifested in Tona, al-halqa’s women, and Rabha. Tona is a good, devoted, caring, thoughtful, and true wife, who tries to satisfy her husband’s desires and needs. The dramatist captures a scene in which reciprocal love and care is revealed.

Almejdoub: O Tona, my greetings came to your ears. Let me enjoy the cold of winter.

Tona: How shall I treat my lover who cared not about his welfare but min. Separation is so difficult to endure and his lovely face is so dear to me.

Almejdoub: O you, passing girls! O you palms of green meadows! You are all beautiful, but I loved only this. Your eyes and eyebrows are black and your sideburns are Hindu. O you, who digs the ground with a stick. Let you speak, O you the crazy-for-love woman.[16]

As to Rabha, she represents the shrewd and unbearable Moroccan woman, who is influenced to the bone by outworn and obsolete beliefs. All she cares for is to eat to her fill and enjoy the adornments of life. She is featured in the following quotation:

Almejdoub: This is her talk…look, she is now going to talk about the house.

Rabha: Why can’t I? you think I live like my ladies.

Almejdoub: After the house…the clothes.

Rabha: yes, I have not dressed like other women.

Almejdoub: And after eating….

Rabha: I have not fed on what other women eat.

Almejdoub: And the furniture?

Rabha: I have not furnished my house like others’.

Almejdoub: This is Rabha’s talk.[17]

Yet al-halqa’s women seem to speak in defense of themselves in the face of Almejdoub’s views in relation to their selves. However, they tend not to see harm in Almejdoub’s views as they are turn out to be wise. Here is a conversation between them and Almejdoub:

Almejdoub: the pigeon has flied higher and higher; and when it landed, it erected on a facile branch. All women behave in the same manner. If one is an exception, she only finds herself incapable

Woman 1: You think women have nothing to say…

Women 2: They hear through their ears…

Almakhzani: O my lady, show what you have.

Woman 1: The love of women is musk from apples

Woman 2: A fragrance smelt in streets.

Woman 1: That who loves it surely dies satisfied.

Woman 2: That who hates it dies surely unhappy.

Almakhzani: When I see horses, I want to ride them.

Almejdoub: When I see old women, I want to repent.[18]

In brief, all the characters approvingly at times and disapprovingly at others seem to interact with Almejdoub’s sayings, which they eventually find interesting and accurate. These characters discuss their lives on cultural and social, political and economic planes. Thus al-halqa becomes a mirror-up to Moroccan society, that is to say, a stage where the cloying and bitter are dealt with collectively, including men and women, young and old. By seeking realism, Saddiki aimed therefore at retrieving both an underground pre-theatrical performance and the artistic climate it created.

At the level of language, the drama could be divided into two sections: one containing Almejdoub’s poems and sayings while the other containing the dramatist’s additions and directions. Almejdoub’s language is “semi” classic. To those early generations, Almejdoub’s poems sounded slight and bloodless, and surprisingly refined, too, but to us whose appetite has taken in his almost-epic-length lyrics a keen appreciation, his poems are compiled to push Homer himself to nod if he were compelled to read his accumulated Quatrain. In my view at least, they are poems of feeling rather than representations of things, and are closer to philosophy than to photography. This Moroccan poet let realism alone, and, like a painter, rarely tried to imitate the external form of reality. He scornfully left out shadows as irrelevant to essences, preferring to paint with words in plain air, with no modeling play of light and shade words, like the brush, could create; and he smiled at Western insistence on the perspective reduction of distant things. He wished to convey a feeling rather than an object, to suggest rather than to represent; it was unnecessary, in his judgment, to show more than a few significant elements in a line; as in early Arabic poems, only so much should be shown as would arouse the appreciative mind to contribute to the esthetic result by its own imagination. The poet valued the rhythm of line and the music of forms infinitely more than the haphazard shape and structure of things. He felt that if he were true to his own feeling it would be realism enough.

Saddiki found it encouragingly emulating and in light of this motivated his characters to speak Almejdounb’s poems. In other words, Almejdoub seems to have linguistically influenced his fellow kinsmen as they appear struggling to mimic him. Saddiki therefore seeks linguistic originality and authenticity. Yet this would have been feasible if only we had not had a hybrid theatre. In this regard, Khalid Amine is critical of Saddiki’s go-it-alone-culture retrieval. He says that “the hybrid formation of the play resists any claim of originality and authenticity even from the part of Saddiki himself, for the play is a hybrid fusion of Western theatrical methods and local techniques of bsat.” He continues, “But Saddiki’s claim of originality, authenticity and the return to tradition sometimes runs the risk of falling into the trap of purity and essentialism.”[19] Undoubtedly, Saddiki in this drama pushes for the retrieval of a lost tradition, which for centuries has honored our ancestors and provided them with a window into knowledge. Saddiki believes that our tradition is suitable for both learning and teaching.

Pr. Khalid Amine has repeatedly maintained in his writings[20]that the transfer of al-halqa into theatre buildings “spells out an underwritten indecision,” which is “part of the predicament of the Moroccan subject,” that “found himself constructed on the borderlines of different narratives: the Western and the local.” Again, he keeps maintaining here and there that “postcolonial theatre has boldly come to terms with the hybrid condition of the Moroccan subject who cannot exist otherwise due to the traumatic wounds that were inflected upon him by the colonial enterprise.”[21] Indeed, al-halqa’s transposition to the stage epitomizes a positive vacillation between two heterogeneous theatrical environments, indeed two theatrical opposites. Saddiki’s play in question clearly shows this vacillation and marriage between East and West, past and present, tradition and modernity. It is here that Hassan Mniai argues that:

[Saddiki] was transformed out of the blue into an advocate of Moroccan/Arabic theatre that would benefit from the potentialities of Western theatre, on the one hand, and, on the other hand, engender its own form through an appeal to legacy and tradition, be it history of a theatrical form or other dramatic essences.[22] [My translation]

Prior the 1970s, a serious debate was started about our theatrical identity in relation to the Other. There was a conflicting interference between two main theatrical tendencies that informed –and continue to inform— different negotiations of traditional performance behaviors like al-halqa. The first tendency saw that the Western model at large should be repudiated in favor of a return to the indigenous performance traditions (which is but another way of returning to pre-theatrical Morocco). Pr. Khalid Amine remarks here that it is this tendency that has led some to the worship of ancestors, constituting eventually a useless quest for purity which amounts to what would be called Arabo-centrism.[23] Truly, this essentialist theatrical enterprise comes alive only when it depends upon a new myth of origin in the name of ‘authentic Arabic/Moroccan Theatre,’ whereas the reality is that these co-called indigenous performing traditions are “diasporic cultural constructs that change time and again and are transformed according to the inner dynamics of folk traditions which are adaptive, fluid and changing.”[24]Armed with this consciousness, Saddiki understood that decolonizing Moroccan theatre from the Western telos does not mean a recuperation of a pure and original performance tradition that pre-existed the French colonial encounter with the Western Other in that this tendency would surely fall in an inevitable essentialism and an Orientalism from within.[25] In his significant study, Migrancy, Culture, Identity, Ian Chambers asks as if waiting to hear a Derridian answer:

“Does there even exist the possibility of returning to an authentic state, or are we not all somehow caught upon an interactive and never-to-be-completed networking where both subaltern formations and institutional powers are subjected to interruption, transgression, fragmentation and transformation?”[26]

Indeed, Derrida ensures that there is no way back to an authentic state. In his terms, the authentic is very much like a ‘cinder’ or a ‘trace’ for it destroys its purity at the very moment of presenting itself.[27]

The second tendency premised itself on the belief that Western theatre is a supreme model opposing its local –and pre-theatrical –counterpart. Similarly, such reading of theatrical identity also generates the same Eurocentric exclusion of other people’s performance traditions. In other words, this tendency elevates the Western theatrical tradition to be a sui generis model worthy of imitation and reproduction. That is to say, Western theatre is a master model, original and accurate. Pr. Khalid Amine comments that the Western theatrical model, however, is more than a dramatic/theatrical space as it is a cultural and discursive one simultaneously. He continues,

Borrowing the Western model without critiquing its exclusive tropes amounts to a new kind of colonialism. In brief, this second position that is held by some Moroccan critics and practitioners, such as Ouzri, falls in another kind of essentialism, that is the European theatre is a unique model that should be disseminated all over the World even at the expense of other peoples’ theatrical traditions, for theatre is no tradition but the western one.[28]

Yet, in the teeth of the essentialist illusion of boundedness, theatre tends to historically evolve through mimetic borrowings, appropriations, and cultural exchanges. Pr. Khalid Amine maintains that “there is no theatre in and of itself” and that the western theatre itself is a hybrid model. Generally, “theatrical art is a hybrid medium that necessitates a transformation of something written on a script into an acoustic and visual world called mise en scéne.”[29]

The widely-held Eurocentric belief of pure and immutable European theatre is premised upon a paradoxical hypothesis, so to speak. As a matter of fact, Europe itself in its entirety is a “mélange” of a plethora of cultures essentially from the backward, uncivilized, and static East.[30]It is this self-contradiction of this “master model theatre” relying upon the “pre-theatre” to theatrically and dramatically feed itself that affords an adequate evidence to deconstruct and reconstruct this Eurocentric discourse. Generally speaking, there are many Islamic and non-Islamic philosophers, scientists, alchemists, and historians from the non-Western territories who have greatly contributed to the making of western civilization during the Renaissance and Enlightenment eras. Remarkably, these were “moments of cultural mixing” when the East was significantly exerting a great impact on all western civilizations.[31]Hence, is not Europe a hybrid culture as well? In truth, the East did not only influence European culture, it also added up highly to its establishment. Hence, Europe is a hybrid culture in itself as it arbitrated its constructs to the driving force of history, that is to say, to dynamisms of borrowings and appropriations.

The argument I am making here is that hybridity is a common cultural feature. From this vantage, Moroccan theatre at present appears to be “construed within a liminal space, on the borderlines between different tropes. It cannot exist otherwise, for it juxtaposes different heterogeneous entities only to emerge as a hybrid drama that is spaced between East and West:”[32]it beautifully fuses in a lofty blend the Western theatrical and the indigenous performance traditions. This hybrid blend is manifested in the very transfer of al-halqa from jema-elfna into modern theatre buildings such as Saddiki’s Mogador in Casablanca, a theatre similar to Western theatre buildings. “Thus,” maintains Pr. Khalid Amine, “the postcolonial condition of Moroccan theatre today is characterized by hybridity as a dominant feature.”[33]In H. Bhabha’s phraseology,hybridity is not only a fusion of two pure moments. It also has to do with the persistent emergence of liminal third spaces that transform, renew, and recreate different kinds of writing out of previous models. In an interview he says that,

As I was saying, the act of cultural translation (both as representation and as reproduction) denies the essentialism of a prior given originary culture, then we see that all forms of cultures are continually in a process of hybridity, but for me the importance of hybridity is not to be able to trace two original moments from which the third emerges, rather hybridity to me is the ‘third space’ which enables other positions to emerge.[34]

According toBhabha, Moroccan theatre today can be construed within that liminal space which emerges between different tropes. “It is a theatre that is informed by an intentional esthetic hybridity as it tends to juxtapose different heterogeneous elements that belong to opposed performing traditions. The effects of hybridity are manifested in its ironic double consciousness.”[35]

Pr. Khalid Amine continues that,

The outcome of a persistent quest is the hybrid transposition of some native performance behaviors such as al-halqa and bsa:t into the theatre building as a western esthetic/cultural space, for an overall refusal of the western theatre building remains an unattainable desire. It is precisely because of this that al-halqa and bsa:t have been transposed to the theatre building. This transposition is not simply a transfer of a performance behavior from jema’ el-fna into a modern theatre building, rather it is a cultural and esthetic negotiation between two different performance traditions. The result of such negotiation is a third space, a hybrid conduct that fuses Self and Other, East and West, popular and modern, and all other bipolar opposites which the hybridized mind imagines to have existed ‘before.’[36]

Informed by the postcolonial Moroccan subject’s hybridized pattern, postcolonial Moroccan theatre today is blending different performing strategies belonging to both Moroccan culture and its Western counterpart. As a result, Moroccan theatre is said to be a hybrid theatre par excellence. “It is no longer an imitation of the western theatre, and it is no more a pre-theatrical form, but a new hybridized theatrical tradition” that is premised on “transposition of all that is used to be conceived of as a pre-theatre to the theatre building.” The magic “openness and free play of Jema’ el-fna are forced upon the rigidity and closure of the western theatrical building.”[37]

Notes:

[1]See Khalid Amine, Moroccan Theatre Between East and West (Le Club du Livre de la Faculté des Lettres et des sciences Humaines de Tétouan, 2000), p, 112.

[2]Quoted in Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 112.

[3]Quoted in Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 112.

[4]See Khalid Amine and Marvin Carlson, “Al-halqa in Arabic Theatre: An Emerging Site of Hubridity” in Theatre Journal, Volume 60, Number 1, March 2008, pp, 71-85.

[5]See Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 113.

[6]Ibid.

[7]Ibid.

[8]Ibid. pp, 113-114.

[9]Ibid. p, 113.

[10]See Tayeb Saddiki, Diwa :n Sidi Abedrrahman Almajdoub (Dar Sattoki Linachr, 1997), p, 61.

[11]See Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 114.

[12]See Hassan Habibi, Tayeb Saddiki: Hayato Masrah (Tayeb Saddiki: A Theatre Story) (Matbaàt Dar al-Nashr, 2011), p, 68.

[13]See Tayyeb Saddiki, Diwa :n Sidi Abedrrahman Almajdoub (Dar Sattoki Linachr, 1997), P, 18. I would like to make it clear that Abderahman’s poetic lines are very difficult to translate into English, yet they surprisingly retain their poeticity and beauty. My translation therefore is only meant to convey some shade of meanings of Abderahman’s sayings.

[14]See Wole Soyinka, Collected Plays 2 (Oxford University Press, 1974) p, 6.

[15]See Diwa:n Sidi Abderahman Almejdoub. P, 52.

[16]Ibid. pp, 15-16.

[17]Ibid. p, 42.

[18]Ibid. pp, 29-30.

[19]See Khalid Amine, “Crossing Borders: Al-halqa Performance in Morocco from the open Space to the Theatre Building” in The Drama Review 45,2 (T170), Summer 2001 (New York University and the Massachusetts Institue of Technology : 55-69.

[20]See for example, Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 129; “Crossing Borders;” “Theatre in Morocco and the Postcolonial Turn” in Interweaving Performance Culture, 09/21/2009.

[21]See for example, Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 129.

[22]See Hassan Mniai, al-masrah al-htifali mina at-taesis ila sina’at al-furja [Moroccan Theatre from Construction to the Making of Spectacle] (Fes : faculty of Letters Publications, 1994), p, 10.

[23]See Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 130.

[24]Ibid.

[25]Ibid.

[26]See Ian Chambers, Migrancy, Culture, Identity (London and New York : Routledge, 1994) p, 74.

[27]Quoted in Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 131.

[28]Ibid. pp, 31-32.

[29]Ibid. p, 132.

[30]See Ella Shohat and Robert Stam, Unthinking Eurocentrism, Multiculturalism and the Media, (London: Routledge, 1994), p, 14.

[31]Ibid.

[32]See Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 132.

[33]Ibid.

[34]See Homi Bhabha, “The Third Space : Interview with Homi Bhabha” in Jonathan Rutherford (ed.), Identity,

Community, Culture, Difference (London: Lawrence and Wighart, 1990), p, 211.

[35]See Moroccan Theatre between East and West, p, 133.

[36]Ibid. pp, 133-134.

[37]Ibid. p, 134.